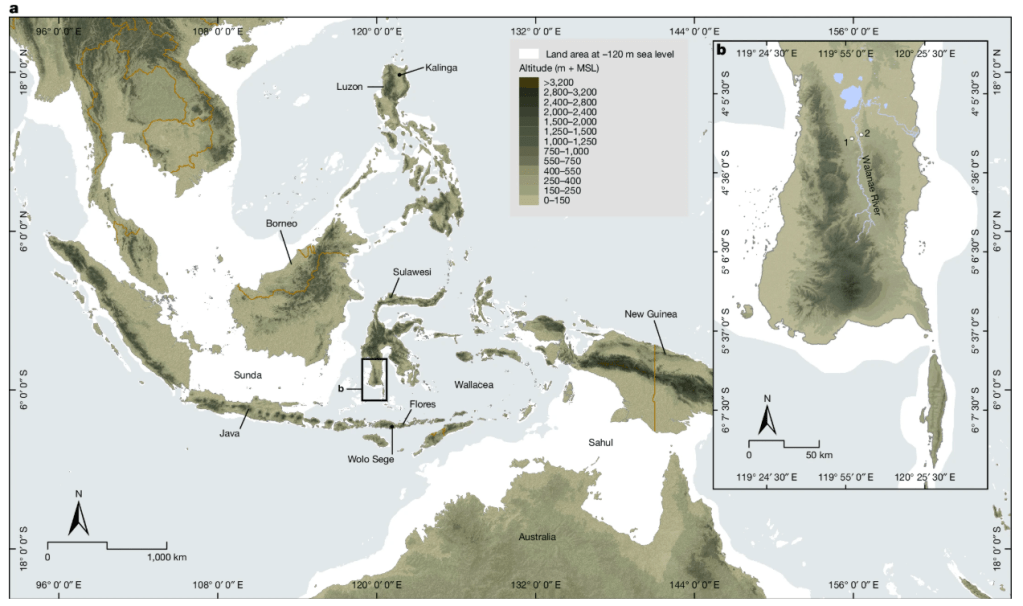

Research at Calio, South Sulawesi, suggests that technological capabilities, spatial dispersal, and human-environment interactions during the early Pleistocene were far more complex than previously assumed.The latest archaeological discoveries at the Calio site in South Sulawesi, as reported by a field team led by senior archaeologist Budianto Hakim from the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia (BRIN), suggest that hominins may have been present on the island of Sulawesi as early as 1.04 million years ago, and possibly as far back as 1.48 million years ago. This is a significant scientific and conceptual finding, not only because it places Sulawesi on par—or even earlier—than Flores and Luzon in the chronology of early human migration to the Wallacea region, but also because it challenges the migration and adaptation narratives that have long been upheld in Southeast Asian prehistoric studies.

What was found?

The research team discovered seven stone artifacts that unambiguously show human modification, buried in old river sand layers of the Walanae Formation (Beru Member Sub-Unit B). The artifacts were made from locally available chert and demonstrate free-hand flaking techniques using hard-hammer percussion. One artifact was even identified as a Kombewa flake—a secondary reduction technique requiring advanced understanding of strike direction and platform.

The layer where the artifacts were found is estimated to date back to the Early Pleistocene based on paleomagnetic data and a combination of Uranium-Serial-Uranium (US-USR) dating and Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) dating on a maxilla fossil of Celebochoerus heekereni found at the same location and depth.

The US–ESR dating model applied in this study—with an estimated age of 1.26 ± 0.22 million years—has been calibrated using modern techniques that account for Uranium diffusion variations. These results reinforce paleomagnetic findings indicating reversed polarity of the rock formation, suggesting a time interval between 1.07 and 1.78 million years ago (between the Olduvai and Jaramillo subchron).

Relevance and implications

If these artifacts are indeed from more than one million years ago, the Calio site represents the earliest evidence of hominin presence in South Sulawesi. This places Sulawesi on par with Flores, where artifacts from the Wolo Sege site have been confirmed to be approximately 1.02 million years old (Brumm et al., 2010), and earlier than Luzon, whose artifacts are dated to 709,000 years (Ingicco et al., 2018).

However, unlike Flores, which has hominin remains such as Homo floresiensis, or Luzon with Homo luzonensis, the findings in Sulawesi have not included hominin fossils. Therefore, the identity of the hominin species in Calio remains speculative. Were they Homo erectus who migrated from mainland Asia? Or perhaps an early representation of another extinct hominin group? Or even the ancestors of H. floresiensis or H. luzonensis?

These questions lead us to broader considerations about the history of colonization in the Wallacea region. This region is an ecological and geographical barrier, a significant sea barrier that theoretically requires seafaring abilities or at least sea crossings that cannot be explained solely by ocean currents or passive dispersal. Therefore, if hominins did indeed reach Sulawesi more than one million years ago, we need to re-examine assumptions about their navigational abilities and technological adaptations.

Why are these findings important?

These findings suggest that early human migration was far more complex than assumed by conventional “out of Africa” models, which rely on gradual migration via land bridges. Wallacea, as an archipelagic zone between the Asian (Sunda) and Australian (Sahul) continents, provides an ideal testing ground for questioning the extent of early hominins’ navigational, technological, and environmental adaptation capabilities.

Also, this finding challenges the chronological biases in Southeast Asian archaeology, which have long been overly focused on Flores and the Philippines. Sulawesi, which is geographically larger and ecologically more complex, may harbor many other important prehistoric sites that have not yet been systematically explored. The importance of this study lies not only in its age but in the need to rewrite the narrative of the colonization of Wallacea, taking into account multi-path and multi-time migration models, with major implications for the reconstruction of hominin evolution in Southeast Asia and Australasia.

The findings at Calio should serve as a springboard for further investigation.

The top priority is to find hominin skeletal remains that can link the artifacts to a specific species. Additionally, further geoarchaeological studies are needed to ensure that the stratigraphic context of the artifacts has not been disturbed by secondary sedimentation processes. Systematic excavations with micro-sedimentological control, organic residue analysis, and geospatial mapping will be crucial. Equally urgent is the development of a more flexible interpretative framework that is less reliant on artifact typology or linear chronology, but opens up space for simultaneous migration and parallel adaptation. Research at Calio, South Sulawesi suggests that technological capabilities, spatial dispersal, and human-environment interactions during the early Pleistocene were far more complex than previously assumed.