The nineteenth century witnessed a profound social and health crisis in industrializing Europe. Rapid urbanization and exploitative labor conditions created overcrowded slums, foul sanitation, and rampant disease among the working classes. In response, public health emerged as a scientific field intimately tied to social justice issues. Thinkers and reformers recognized that preventing disease and improving health meant addressing the appalling living and working conditions endured by the poor.

This essay analyzes how labor conditions and sanitation in 19th—and early 20th-century Europe catalyzed the development of public health as a discipline grounded in social justice ideals. It focuses on the contributions and critical insights of Friedrich Engels, Edwin Chadwick, and Americans like Charles-Edward Amory Winslow—three figures who, in different ways, linked health with labor rights, sanitation reform, and social equity.

Engels exposed the deadly toll of industrial exploitation on worker health and introduced the moral indictment of “social murder.” Chadwick marshaled data and engineering to enact sanitary reforms to save lives and uplift the poor (albeit through a utilitarian lens). In the early 20th century, Winslow synthesized these threads by broadly defining public health not only as sanitation and disease control, but as the “social machinery” to ensure a decent standard of living for all. Together, their work shaped public health’s scientific and political development as a discipline committed to labor-class well-being and social justice.

This essay further explores how their findings and advocacy influenced public health’s evolution and draws connections between their ideas and current public health challenges of inequality. In doing so, it offers a critical synthesis of how the sanitation of working-class environments catalyzed scientific responses and how those early frameworks still inform public health responses to labor and social inequality today.

Part 1. Industrial Labor and Sanitation in 19th-Century Europe: A Context for Reform

By the mid-1800s, Europe’s great industrial cities had become infamous for their “hellish” living conditions and health threats. Factories drew thousands of rural migrants into urban centers that lacked adequate housing, clean water, or sewage systems. Entire families crowded into single tenements and cellar dwellings, often “penned in dozens into single rooms” with scarcely any ventilation.

In the working-class quarters of cities like Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, and London, refuse filled the unpaved streets, and seeping cesspools and dung heaps fouled the air. Basic necessities were in short supply: the poor wore ragged, germ-ridden clothing and subsisted on adulterated food of poor nutritional value. To make matters worse, laborers toiled for long hours in dangerous factories and mines, draining their physical energy and exposing them to injuries and occupational diseases. As Friedrich Engels described it, “all conceivable evils” were heaped upon the urban poor – from toxic environments and exhausting work to constant economic insecurity. Those who somehow survived these hardships often succumbed early to infectious disease. Epidemics of tuberculosis (“consumption”), typhus, cholera, smallpox, and other illnesses swept through the slums with devastating regularity. One contemporary observer noted that by around 1840, in cities of 100,000 or more, the average lifespan was only about 26 years – a shocking statistic that underscored the lethal impact of urban poverty and overcrowding on health.

These dire conditions did not go entirely unnoticed by the educated classes and authorities. Some feared that the “disease, dirt, deprivation, and death” stalking the industrial poor might eventually threaten social order. Recurrent cholera outbreaks, starting in the 1830s, were especially galvanizing. Cholera struck rich and poor alike with terrifying speed, exposing how untenable the status quo had become. In Britain, the specter of cholera prompted municipalities to form local Boards of Health and sent physicians into the slums to investigate causes. It also fostered a new recognition that urban health was a matter of public concern requiring collective action – both to prevent political instability and to achieve basic social justice. Against this backdrop, a nascent public health movement took shape, championed by social critics and reformers who argued that society had an obligation to improve living and working conditions. Foremost among these were Friedrich Engels and Edwin Chadwick in the 1840s, followed by others in subsequent decades. Their efforts would lay the groundwork for public health as a field devoted not only to controlling disease, but to addressing the social ills that cause disease. The following sections examine how Engels’s searing moral critique of labor conditions, Chadwick’s sanitary reforms, and Winslow’s expansive vision of public health each contributed to the emergence of public health science rooted in social equity.

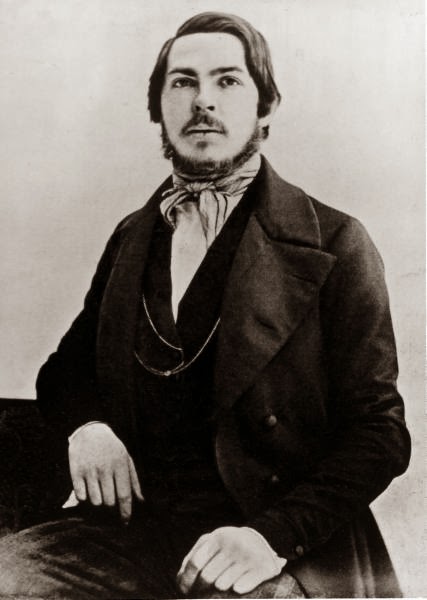

Part 2. Friedrich Engels: Exposing “Social Murder” and the Social Determinants of Health

In 1845, the young German political economist Friedrich Engels published Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England (The Condition of the Working Class in England), a seminal investigation of how industrial labor and poverty were destroying the health and lives of workers. Living in Manchester and other British industrial centers in the early 1840s, Engels directly observed the misery of the urban proletariat. He found entire working-class districts shrouded in soot and “vitiated atmosphere,” with foul-smelling open sewers and heaps of garbage lining the streets.

In grim, narrow alleyways, families were packed into damp cellar hovels “that are not waterproof from below” or drafty attics that “leak from above,” lacking light or fresh air. The working people trapped in these conditions, Engels noted, could hardly ever be healthy or long-lived. Indeed, he cited official statistics to illustrate the toll: in one district of Leeds, for example, there were three deaths for every two births, signaling inevitable decline. Epidemics were constant companions of the poor; diseases like tuberculosis, typhus, and scarlet fever cut swaths through overcrowded neighborhoods.

Crucially, Engels looked beyond the mere presence of disease to interrogate its social causes. He argued that these appalling health conditions were not simply bad luck or personal failings, but the direct result of the capitalist industrial system and the negligence of the ruling class. In his view, factory owners and governing elites knowingly subjected workers to unhealthy environments in the pursuit of profit, while providing meager wages that left workers malnourished and vulnerable.

Engels famously condemned this dynamic as a form of murder – “social murder” perpetrated not by individual assailants, but by society itself. As he wrote, when society places workers in conditions that inevitably lead to an early and unnatural death, “its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder”. Unlike an ordinary murderer, the perpetrators of social murder are unseen and their actions appear indirect – “no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one” – yet Engels insisted the moral responsibility is the same. Society “daily and hourly commits” this crime by forcing people to live and labor in deadly conditions, “undermining the vital force” of workers and “hurrying them to the grave before their time,” Engels charged. This fiery indictment made plain that the appalling health of the working class was not an inevitable fact of nature but a human-inflicted injustice that demanded political action to remedy.

Engels’s Condition of the Working Class was groundbreaking in linking public health outcomes to social and economic determinants. Long before the term “social determinants of health” existed, Engels systematically documented how factors like poverty wages, poor housing, inadequate diet, polluted air, and dangerous labor all interacted to produce ill health. A recent analysis noted that Engels “identified virtually every social determinant of health now found in contemporary discourse”. For example, Engels detailed how malnutrition (“want of proper nourishment”) made workers susceptible to disease, how filthy neighborhoods bred infection, and how job insecurity and stress led to mental despair.

In effect, Engels treated the slums and factories of Victorian England as a vast epidemiological experiment, gathering qualitative and quantitative evidence that health is inextricably linked to social conditions. This was a radical departure from prevailing narratives that blamed the poor for their own ill health or saw disease strictly as a biomedical phenomenon. By reframing workers’ high mortality as a social crime, Engels injected a powerful moral urgency into public health discourse: society must change if these needless deaths are to be prevented.

The impact of Engels’s work resonated beyond revolutionary circles. His findings were read by public officials and fellow reformers, and they reinforced the calls for sanitary and social reforms. Decades later, famed physician Rudolf Virchow (a contemporary of Engels) echoed the same sentiment, declaring that “politics is nothing but medicine at a larger scale” and that epidemics could only be eliminated by addressing poverty and inequality. Virchow’s agreement lent scientific credence to Engels’s observations.

More directly, Engels’s fusion of data and moral argument helped inspire the field of social medicine and laid the intellectual groundwork for what we now call health equity. The notion that widespread ill health among the poor constitutes a societal failing remains a cornerstone of public health ethics. Indeed, calls for social justice in health today often hark back to Engels’s concept of social murder.

In recent years, there has been a “reemergence” of the social murder concept in academic literature, invoked to describe events like the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire in London or the disproportionate deaths of the poor during the COVID-19 pandemic. One public health commentary remarked that the “social murder observed by Engels in 1845 is still going on today,” noting that the poorest in society died at much higher rates from COVID-19 – a 21st-century replay of Victorian patterns. Thus, Engels’s critical insight – that health is a matter of social justice – remains profoundly influential. It provided public health with a moral compass focused on protecting the vulnerable and confronting the structural causes of disease.

Part 3. Edwin Chadwick: Sanitary Science and the Politics of Reform

While Engels agitated for revolutionary change, in the same era a very different figure, Edwin Chadwick, was spearheading pragmatic reforms to clean up cities and improve public health. Sir Edwin Chadwick was a British lawyer and civil servant who became a key architect of the sanitary movement in the 1840s. Unlike Engels, Chadwick approached public health as an administrative and engineering challenge rather than a class struggle. Nonetheless, his work also emerged from the recognition that the appalling conditions of the laboring poor were neither acceptable nor inevitable, and that systematic action could save lives.

Chadwick’s 1842 Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain was a landmark in public health science and policy. Running hundreds of pages, this report marshaled an unprecedented array of statistics, survey findings, and eyewitness accounts to demonstrate the extent of filth and disease among Britain’s workers. Chadwick and his team of investigators traveled to industrial towns, documenting overflowing cesspits, stagnant water, open sewers, and the utter lack of drainage in working-class neighborhoods. They compiled data on death rates and life expectancy, revealing stark health disparities between the impoverished laborers and the more affluent classes. For example, Chadwick showed that in Liverpool, the average age at death for gentlemen was far higher than for laborers, quantifying inequality in lifespans. These facts, Chadwick believed, would force the hand of policymakers by making the connection between insanitary environments and poor health irrefutable.

In his report and subsequent advocacy, Chadwick laid out a clear causal narrative: poverty alone was not the root cause of disease—“filth” was. He argued that squalid, decaying surroundings led directly to illness: bad air (“miasma”) from refuse and sewage caused infectious fevers; contaminated water spread cholera and typhoid; and overcrowding fostered tuberculosis. Disease then produced poverty by incapacitating breadwinners, creating a vicious cycle.

Notably, Chadwick observed that many behaviors often blamed on the poor (such as drunkenness or violence) were in truth results of their misery, not the cause: these vices “were consequences rather than causes of the conditions of poverty,” he wrote. His report presented poverty as a symptom of ill health and ill environment, rather than an inherent moral failing. This framing was instrumental, as it suggested that by cleaning up the environment, one could break the cycle of disease and destitution.

Chadwick’s principal recommendations were thus technocratic but bold for their time: provide clean water, remove sewage and refuse, and improve housing ventilation. Chadwick was calling for the creation of the urban infrastructure that we now take for granted: “improved drainage and provision of sewers,” the “removal of all refuse from houses, streets and roads,” and “the provision of clean drinking water”. He also urged that every town appoint a medical officer of health to oversee sanitation and disease prevention – an early template for local public health departments.

Chadwick buttressed his reform proposals with a cost-benefit argument aimed at the political establishment’s pocketbook. As a former Poor Law Commissioner, he was acutely aware that sickness and high mortality among workers imposed heavy costs on taxpayers who funded poor relief for widows, orphans, and disabled laborers. “Chadwick’s argument was economic,” as the UK Parliament later summarized: he believed that improving the health of the poor would ultimately reduce the numbers needing poor relief and thus save public money. Preventing a worker’s premature death from typhus, for instance, might prevent his family from falling into destitution that the parish would have to alleviate. This utilitarian rationale made sanitation reforms more palatable to lawmakers.

Indeed, Chadwick convinced many that “money spent on improving public health was therefore cost effective, as it would save money in the long term”. Armed with both moral and economic arguments, Chadwick – alongside activists in the Health of Towns Association – pressed Parliament for legislative action. The result was the Public Health Act of 1848, Britain’s first significant public health law, which created a Central Board of Health and empowered local authorities to build sanitary systems. Chadwick was appointed to the Central Board (along with social reformer Lord Shaftesbury and physicist John Simon), officially inaugurating governmental public health administration in England.

Chadwick’s contributions to public health are immense. He helped institutionalize the idea that the government has a responsibility for the health of its citizens, especially through environmental interventions. His 1842 report became a foundational text for sanitary science, influencing public health reforms across Europe and in the United States. The measures he championed – sewers, clean water, garbage removal – led to dramatic reductions in infectious disease in the late 19th century.

For example, cities that implemented modern sanitation saw cholera and typhoid rates plummet. “There is no doubt that Chadwick’s interventions were enormously beneficial [and] saved many lives, redressing health inequalities to some extent,” as one medical historian noted. By improving the physical environment of the poor, Chadwick’s work did promote a degree of social equity in health outcomes – fewer people died of preventable diseases, and the gap in survival between rich and poor narrowed modestly.

Yet, Chadwick’s approach had limits that drew criticism both then and now. Intentionally, he steered clear of addressing poverty or labor exploitation directly. In fact, Chadwick maintained that destitution was largely a byproduct of disease, not a root cause. He even rejected contemporaries’ claims that low wages or lack of food were killing workers.

Notoriously, he refused to include a category of “starvation” in mortality statistics, arguing “it was impossible for a person to starve to death in London” – to admit otherwise, he felt, would signal a failure of his sanitary agenda and the Poor Law system. This mindset exemplified Chadwick’s belief that environmental engineering and basic public services could solve the health crisis without altering the economic hierarchy.

Thus, while Engels decried the capitalist system for “social murder,” Chadwick spoke of foul drains and unchecked filth. The two perspectives were “entirely different but potentially complementary approaches to tackling health inequalities,” as physician Iona Heath observed. Engels advocated political action and fundamental social change; Chadwick offered technical solutions and bureaucratic reform.

Chadwick’s work did not challenge the class structure or the meager wages of the laboring poor. Consequently, his sanitary reforms “did nothing about poverty as such or about the unresolved injustice it expresses,” even if they alleviated some suffering. In contrast, Engels was “primarily concerned with social justice” and helped inspire movements that eventually improved workers’ political power and living standards. Heath argues that neither the purely technical nor the purely political approach was sufficient alone – “both are required” for lasting progress.

From a modern standpoint, Chadwick can be seen as both a pioneer of evidence-based public health and a product of Victorian paternalism. He treated sanitation as a means to achieve “political stability and social justice” through efficiency and science, equating clean water and sewers with a stable, more just society, albeit on bourgeois terms. This framing helped sell public health to the powers of the day, even if it downplayed more radical demands of the working class.

Importantly, Chadwick’s legacy in public health science is the methodology of surveying populations, using statistics to identify health problems, and implementing large-scale interventions. These remain core practices in public health. At the same time, Chadwick’s critique underscores a lesson that also carries forward: purely technical health fixes without addressing underlying social inequities can only go so far. The next generations of public health leaders, such as Charles-Edward Winslow, would strive to integrate the sanitary-engineering tradition of Chadwick with the social justice consciousness voiced by Engels.

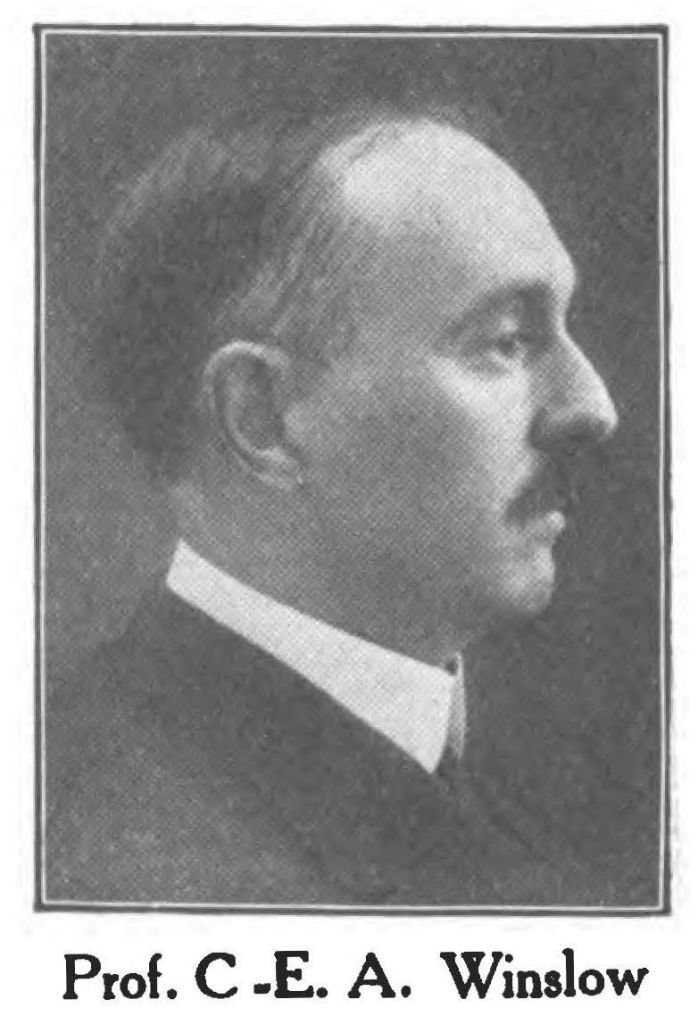

Part 4. Charles-Edward A. Winslow: Defining Public Health with Social Equity at Its Core

By the early twentieth century, the field of public health had evolved in scope and sophistication, thanks in part to advancements in microbiology (germ theory), the establishment of municipal health agencies, and the accumulation of sanitary infrastructure. Charles-Edward Amory Winslow (1877–1957), an American bacteriologist and public health leader, emerged as a pivotal figure who formalized public health as a scientific discipline while explicitly emphasizing its social dimensions. Winslow’s career and writings show the influence of the 19th-century sanitary movement and social medicine on public health’s intellectual framework. Educated in the Progressive Era, Winslow believed in applying science to social problems and was deeply committed to health as a public responsibility. In 1920, he authored a classic definition of public health that endures today – a definition that crystallized the field’s dual commitment to disease prevention and social betterment.

Winslow defined public health as “the science and the art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health and efficiency through organized community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing service for the early diagnosis and preventive treatment of disease, and the development of the social machinery which will ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health.”

This remarkably comprehensive definition (published in the journal Science in 1920) weaves together the strands of public health’s development: environmental sanitation (echoing Chadwick), control of infectious diseases (the fruits of germ theory and epidemiology), health education and medical services (reflecting early 20th-century public health practice), and social reforms to assure everyone an adequate standard of living (evoking Engels’s focus on the social roots of illness).

Winslow even added that public health should enable citizens to realize “their birthright of health and longevity”. In other words, health is a fundamental right of all, and the role of an organized society is to guarantee the conditions in which people can be healthy. By including the improvement of social and economic conditions in the very definition of public health, Winslow firmly grounded the field in a social justice mission. As a retrospective commentary noted, Winslow’s 1920 definition “helped to shape the discipline and is still, 95 years later, cited as the standard” for what public health encompasses. It directly influenced the World Health Organization’s famous 1948 definition of health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being.

Winslow’s own work exemplified this broad, justice-oriented approach to public health. After training in bacteriology (under William H. Sedgwick, one of America’s first sanitary science pioneers), Winslow became the founding director of Yale University’s Department of Public Health in 1915. He insisted that public health professionals needed expertise both in the laboratory and in community interventions. During his long tenure at Yale, Winslow engaged with almost every facet of public health: he conducted research on water purification to prevent typhoid, studied garbage disposal in cities, examined occupational hazards (“workplace threats to health”), investigated housing conditions, and advocated for better nutrition and poverty relief. As one profile recounts, his interests ranged from “typhoid and public water supplies; garbage disposal in big cities; … workplace threats to health; … the air quality in schools; food poisoning; poverty as a factor in disease; and housing as a public health issue”. This catalog of topics shows Winslow’s recognition that health must be protected in factories, homes, and communities. In essence, he carried forward Chadwick’s concern for sanitation and Engels’s concern for social conditions, wrapping them into a unified public health agenda.

Perhaps most illustrative of Winslow’s commitment to social equity was his work on housing in New Haven. Believing that inadequate housing was hazardous to physical and mental health, Winslow took action beyond academia. He served for 20 years as chair of the local Housing Authority, during which time he was primarily responsible for getting 2,500 apartments built for low-income residents. This was a concrete achievement in improving living conditions for the poor, ensuring, as his definition would put it, a standard of living adequate for health.

Winslow also pushed for progressive health legislation at the state level and helped create the Connecticut State Department of Public Health. Nationally, he was a leader in the American Public Health Association and promoted professionalization and education in public health. In all these roles, Winslow epitomized that public health is an organized, collective endeavor to uplift community well-being, especially for those most vulnerable.

Winslow’s contributions influenced the trajectory of public health science in several key ways. First, by defining the field so broadly, he set an expectation that public health officials must engage in technical disease control and address social determinants. This helped pave the way for later public health initiatives tackling issues like nutrition, housing codes, workplace safety regulations, and school health education–all areas beyond pure sanitation or medicine. Second, Winslow’s academic leadership helped establish public health as an interdisciplinary science. He mentored generations of public health professionals who fanned out to lead health departments and teach at other universities, propagating his ideals. Third, Winslow’s insistence on evidence-based interventions (in the lab or the field) reinforced the scientific rigor of public health practice. Yet he always coupled that science with a humanitarian outlook. In a 1923 book, he wrote that the great public health campaign of modern times must be evaluated not just by bacteria counts or death rates, but by “the extent to which it has contributed to the relief of human suffering and the increase of human happiness.” This reflects the marriage of science and compassion at the heart of Winslow’s philosophy.

Winslow provided the intellectual bridge between the 19th-century sanitary reformers and the modern public health system, ensuring the field remained rooted in social conscience. He echoed Chadwick in emphasizing environmental sanitation and echoed Engels (and Virchow) in affirming that social policy and health are intertwined. By the mid-20th century, thanks in part to Winslow’s influence, public health had firmly adopted the view that equity is a core value that protects the health of the poor and working classes, and is both a scientific and moral imperative. This ethos is clearly visible in the post-World War II era with the rise of welfare states, social medicine, and international health organizations concerned with poverty and development.

Part 5. Public Health as Social Justice: Influence on Science and Modern Echoes

The efforts of Engels, Chadwick, and Winslow, though different in strategy and ideology, collectively forged public health into a discipline deeply concerned with social justice for laboring populations. Each contributed a piece to the foundation of public health science and policy. Engels injected a searing moral analysis, highlighting exploitation and inequality as fundamental causes of ill health and demanding political solutions. Chadwick built the case for sanitary intervention, demonstrating with data that public action could prevent disease and creating the first structures of public health governance. Winslow synthesized these lessons, broadly defining public health to include social welfare and enshrining that health for all is a societal goal. The impact of these contributions on the scientific and political development of public health has been lasting.

Scientifically, recognizing environmental and social determinants led to new fields of inquiry from epidemiology and demography in the 19th century to social epidemiology and health disparities research today. Chadwick’s work, for instance, directly influenced the emergence of epidemiological surveillance; his use of mortality statistics was expanded by William Farr and others to track patterns of disease by occupation, class, and location, which is a practice that continues in modern public health data systems. Engels’s approach prefigured the standard of qualitative research and community-based assessments in public health studies of social conditions.

We see his legacy in contemporary research on social determinants of health, which repeatedly finds that poverty, housing, education, and job conditions are key predictors of outcomes, just as Engels documented in 1845. Winslow’s broad framework anticipated the multi-disciplinary research of today’s public health (encompassing environmental science, sociology, economics, and medicine). His call for “social machinery” to ensure health correlates with what public health researchers now advocate as a “Health in All Policies” approach, integrating health considerations into housing, labor, and economic policies.

Politically, the legacy of these pioneers is evident in how public health has been championed as a matter of social equity by governments and global bodies. The reforms that Chadwick and his contemporaries set in motion in the 1800s, such as municipal sewer systems, public water works, housing regulations, and labor protections, became the backbone of public health infrastructure in developed countries. These advances saved millions of lives and are often cited as the most significant public health achievements. More subtly, they ingrained the idea that the government has a role in safeguarding the essential well-being of citizens, especially the poor. This was a radical notion in the 1840s; today it underpins public health and social policy in many nations (though debates continue over the extent of that role).

The influence of Engels’s and Winslow’s ideals can be seen in incorporating social justice language into public health missions. For example, Sir Michael Marmot’s 2010 review of health inequalities in England explicitly stated: “Reducing health inequalities is a matter of social justice.” Marmot argued that “inequalities that are preventable by reasonable means are unfair” and must be addressed, essentially reasserting Engels’s principle in modern terms.

In 2008, the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health concluded, “Social injustice is killing people on a grand scale,” directly linking disparities in health outcomes to unjust social arrangements. Such pronouncements echo Engels’s 19th-century outrage, albeit in the measured tone of international policy. They also reflect Winslow’s vision that society should organize itself to guarantee health as a right.

Current public health challenges reveal how far we have come and how these early frameworks are still urgently relevant. On the one hand, the sanitary reforms initiated in the 19th century have eliminated mainly the kind of environmental squalor Chadwick battled in countries with developed infrastructure. Outbreaks of cholera from contaminated water, once a regular scourge, are rare in those settings. Occupational health has also improved – labor rights struggles (partly informed by Engels’s and Marx’s influence) led to regulations on working hours, safety standards, and child labor laws, reducing some of the most egregious harms of industrial work.

On the other hand, stark health inequalities persist both between and within countries, often aligned with class, race, and working conditions, much as they did in Engels’s time. The COVID-19 pandemic is a case in point. Lower-income workers, often in “essential” service jobs that could not be done from home, experienced higher rates of infection and death. In England, the most socioeconomically deprived areas saw more than double the COVID-19 mortality rate of the least deprived areas.

A commentator noted that if Engels witnessed this, he might label it “21st-century social genocide,” a hyperbolic term to stress the severity of preventable inequality in health outcomes. Similarly, issues like air pollution and climate change disproportionately affect poor and working-class communities worldwide, reminiscent of the way 19th-century factory smoke choked the slums. Occupational hazards have not vanished either; they have shifted to different sectors and to the global South, where sweatshop workers and miners face conditions not unlike those of 1840s England. Public health professionals today continue to advocate for these workers’ rights and safety, in the spirit of linking labor conditions to health.

Another area of modern resonance is the global movement for clean water and sanitation in low-income countries. Essentially, this is Chadwick’s sanitary revolution being carried to places that never had the benefit of Victorian reforms. Organizations promoting Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) interventions apply Chadwick’s logic: provide latrines, sewers, and potable water to prevent diarrheal diseases and other infections. The ethos is practical and rooted in justice (everyone deserves basic sanitation). In this sense, Chadwick’s legacy is alive in global health efforts to close gaps in infrastructure that underlie health disparities between rich and poor nations.

The early framework of public health also continues to shape its responses by emphasizing community and prevention. Winslow’s definition, highlighting “organized community efforts,” manifests in how public health tackles contemporary problems like HIV/AIDS, substance abuse, or obesity, through community education, outreach, and building supportive social environments. When modern public health campaigns address issues such as housing quality (e.g., reducing lead exposure in old paint) or income security (e.g., advocating for living wages because of health benefits), they are walking the path first charted by Engels and Winslow, connecting material living conditions with health outcomes.

Crucially, the field of public health has increasingly recognized that technical fixes and medical care, while important, cannot produce health equity without social change. This recognition is a direct intellectual inheritance from the 19th-century debates between figures like Chadwick and Engels. For example, Iona Heath’s 2007 commentary lamented that even the best healthcare system cannot offset the “lottery of social conditions” that makes some people sick and poor. She wrote that adequate sewers and modern medicine are “untouched by [the] profound social injustice” that leaves specific populations with diminished opportunities and health prospects. Her conclusion – that we must “get tough on the causes of health inequality” by addressing social injustice – could not be more aligned with Engels’s standpoint. At the same time, she acknowledges the necessity of the sanitary and technical advances that Chadwick spearheaded. Thus, the dual legacy informs today’s comprehensive approaches: combining public health engineering (vaccination, sanitation, etc.) with advocacy for healthier social policies (education, poverty reduction, anti-discrimination efforts).

In sum, the history of public health science cannot be separated from the history of social justice struggles. The labor conditions and sanitary crises of 19th-century Europe forced open a new understanding that health is a social mirror. Figures like Engels, Chadwick, and Winslow were instrumental in forming and translating that understanding into action. Their early frameworks – whether it was Engels’s concept of social murder, Chadwick’s sanitary utopianism, or Winslow’s expansive definition of health – still challenge and guide public health practitioners to tackle the root causes of disease in social inequity. As long as poverty, unsafe working conditions, and inadequate living standards continue to impair health, the foundational insights of those pioneers will retain their urgency.

The DNA of Public Health Today

The emergence of public health as a scientific field in the 19th and early 20th centuries was inseparable from the quest for social justice for Europe’s laboring populations. In the crowded tenements and grim factories of the Industrial Revolution, reformers found not only the breeding grounds of epidemics but also a profound moral calling to protect human life and dignity. Friedrich Engels, Edwin Chadwick, and Charles-Edward Winslow each illuminated a different facet of that calling.

Engels exposed the cruel contradiction of modern progress – an economy that created wealth for a few at the cost of hunger, disease, and early death for the many – and he insisted that this was a political crime that society could and should prevent. Chadwick, horrified by the waste of life he saw in filthy urban slums, demonstrated that rational public administration and engineering could eliminate immense amounts of disease and suffering among the poor. Winslow, inheriting a world already improved by sanitation and bacteriology, carried the torch forward by ensuring that public health remained focused on “the social machinery” needed to uplift everyone’s health, rich or poor. Together, these thinkers and activists transformed public health from ad hoc responses to plagues into a coherent field driven by data, science, and a commitment to equity.

Their influence is plainly visible in the DNA of public health today. Every time a city builds sewers or a slum upgrading project brings clean water to a shantytown, Chadwick’s spirit lives on. Every time health officials speak out about poverty, inequality, or unsafe labor practices as hazards to health, they are channeling Engels’s outrage and Winslow’s ideals.

Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic and other contemporary challenges have powerfully reaffirmed that public health is fundamentally about solidarity with the most vulnerable – be they essential workers lacking paid sick leave or communities of color facing environmental pollution. These issues echo the 19th-century labor and sanitary issues in new forms. The early public health pioneers taught us that science and policy must work in tandem to address such problems: collecting evidence of harm, devising interventions (from vaccines to ventilation to social welfare), and fighting for their implementation.

The journey from the soot-choked streets of 1840s Manchester to the global health initiatives of today has confirmed that health advances occur when society confronts injustice. Public health science, at its best, is far more than the study of microbes or the statistics of mortality – it is “a vision of social justice as the foundation of public health”. Engels gave voice to that vision by declaring it intolerable that one class dies decades earlier than another. Chadwick operationalized that vision by proving that enlightened governance can prevent needless deaths among the poor. Winslow enshrined that vision by defining the field around the principle of health for all.

As we grapple with health disparities and new public health threats, the lessons from those early advocates remain vital. They remind us that public health began as a radical act of compassion and justice, and that its true north has always been to ensure that the benefits of a healthy life are shared equitably across society. In honoring their legacy, we reaffirm a simple truth: the people’s health is indeed the highest law, measured not only by germ-free water and low disease rates, but by how fairly and humanely a society cares for all its members.

References

- Chadwick, E. (1842). Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Engels, F. (1845). The Condition of the Working Class in England. Leipzig: Otto Wigand. (Translated from German, 1887).

- Govender, P., Medvedyuk, S., & Raphael, D. (2023). 1845 or 2023? Friedrich Engels’s insights into the health effects of Victorian-era and contemporary Canadian capitalism. Sociology of Health & Illness, 45(8), 1609–1633. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13676

- Heath, I. (2007). Let’s get tough on the causes of health inequality. BMJ, 334(7607), 1301. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39247.502813.59

- Kemper, S. (2015, June 2). Public health giant: Remembering the man who launched public health at Yale a century ago still influences the field. YaleNews. https://news.yale.edu/2015/06/02/public-health-giant-c-ea-winslow-who-launched-public-health-yale-century-ago-still-influe

- Medvedyuk, S., Govender, P., & Raphael, D. (2021). The reemergence of Engels’ concept of social murder in response to growing social and health inequalities. Social Science & Medicine, 289, 114377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114377

- Morley, I. (2007). City chaos, contagion, Chadwick, and social justice. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 80(2), 61–72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18160991/

- Riley, M. (2020). Health inequality and COVID-19: The culmination of two centuries of social murder. British Journal of General Practice, 70(697), 397. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X711965

- UK Parliament. (n.d.). The 1848 Public Health Act. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/about-the-group/public-administration/the-1848-public-health-act/

- Winslow, C.-E. A. (1920). The Untilled Fields of Public Health. Science, 51(1306), 23–33. DOI: 10.1126/science.51.1306.23