In an era dominated by digital interconnectivity, social media platforms have emerged as vital arenas for public discourse and information exchange. Among these platforms, Meta (encompassing Facebook, Instagram, and Threads) and X (formerly Twitter) hold unparalleled influence. Their algorithms and moderation policies shape how information is disseminated, consumed, and understood—with significant implications for science communication. Recent algorithmic overhauls and a shift toward community-driven content moderation have brought these issues to the forefront, sparking debates about their effects on scientific dialogue and public understanding of factual information.

Algorithmic Evolution and its Impact

Algorithms are the unseen architects of social media, curating the content users encounter and thereby influencing public opinion. Meta and X use algorithms designed to maximize engagement, optimizing for metrics such as likes, shares, and comments. However, these priorities often clash with the goals of science communication, which relies on nuanced, evidence-based content that may not generate viral appeal.

X, under Elon Musk’s leadership, implemented algorithmic changes in 2024 aimed at increasing user interaction. These updates emphasized replies and conversational threads, fostering dynamic discussions. While this approach encourages user engagement, it can inadvertently elevate sensational or polarizing content over well-reasoned scientific discourse. Meta’s similar emphasis on engagement-driven algorithms, including updates in 2024 that altered how content is ranked, has faced criticism for reducing the visibility of rigorous but less ‘clickable’ scientific posts.

The result? A digital environment where the algorithms favor the provocative over the precise, potentially sidelining critical scientific information. Studies on algorithmic amplification have shown that sensationalism often outpaces accuracy in reaching audiences, leading to the marginalization of evidence-based discourse on urgent issues like climate change, vaccine safety, and public health.

Recent algorithmic overhauls and a shift toward community-driven content moderation have brought these issues to the forefront, sparking debates about their effects on scientific dialogue and public understanding of factual information.

Tweet

The Transition to Community-Driven Moderation

Content moderation has always been a contentious issue for social media platforms, balancing free expression against the need to curb misinformation and harmful content. Historically, platforms like Meta relied on professional fact-checkers and AI systems to monitor posts. However, in January 2025, Meta transitioned to a community-driven approach inspired by X’s Community Notes system.

This new model invites users to add contextual notes to posts they perceive as misleading, crowdsourcing the moderation process. Meta’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, described the initiative as a step toward enhancing free expression while addressing censorship concerns. Similarly, X’s Community Notes—introduced under Musk’s leadership—allow users to collaboratively provide additional context to tweets flagged as potentially misleading.

While these systems aim to democratize content moderation, their effectiveness hinges on the active participation of informed users and the platforms’ ability to mitigate bias. The risk lies in the uneven quality of user-generated notes, which may lack the rigor of professional fact-checking. Furthermore, complex scientific topics often require expert analysis to ensure accurate representation, a standard that community-driven systems struggle to meet.

Implications for Science Communication

The confluence of algorithmic changes and community-driven moderation poses both challenges and opportunities for science communication:

- Visibility of Scientific Content: Engagement-focused algorithms often deprioritize nuanced scientific content in favor of more emotionally charged or polarizing posts. Consequently, important research findings and public health updates risk being overshadowed by misinformation or entertainment-focused content (Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, 2018; Pennycook et al., 2020).

- Proliferation of Misinformation: Community-driven moderation can be a double-edged sword. While it empowers users to address misinformation, the absence of professional oversight increases the likelihood of inaccuracies in flagged posts. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation about vaccines and treatments spread rapidly, exacerbated by delays in providing accurate corrections (Chou et al., 2020; Lazer et al., 2021).

- Erosion of Public Trust: The decline in the visibility of authoritative scientific sources, coupled with the prevalence of conflicting information, undermines public trust in science. When users encounter unverified claims alongside poorly contextualized notes, they may struggle to discern credible information, fostering skepticism (Lewandowsky, Ecker, & Cook, 2017; Vraga & Bode, 2018).

- Impact on Scientists’ Engagement: Platforms that prioritize sensationalism over substance may alienate scientists, discouraging them from engaging with the public online. This withdrawal further reduces the presence of credible voices in digital spaces, leaving room for misinformation to proliferate (Jarreau et al., 2019; Brossard & Scheufele, 2013).

Learn from Past: COVID-19 and Social Media’s Role

The COVID-19 pandemic exemplified the dual-edged nature of social media in science communication. Platforms like X and Meta became crucial for disseminating public health information but also served as conduits for misinformation. Studies revealed that community-driven moderation systems—such as X’s Community Notes—achieved mixed success. While some misinformation was effectively flagged and contextualized, delays in adding accurate notes and low user engagement limited the system’s overall impact.

This period also highlighted the limitations of algorithms prioritizing engagement. Posts that were scientifically inaccurate but emotionally evocative often outperformed accurate but less sensational content, demonstrating the challenges of aligning platform incentives with public health priorities.

The Promise of Federated Social Media: Bluesky?

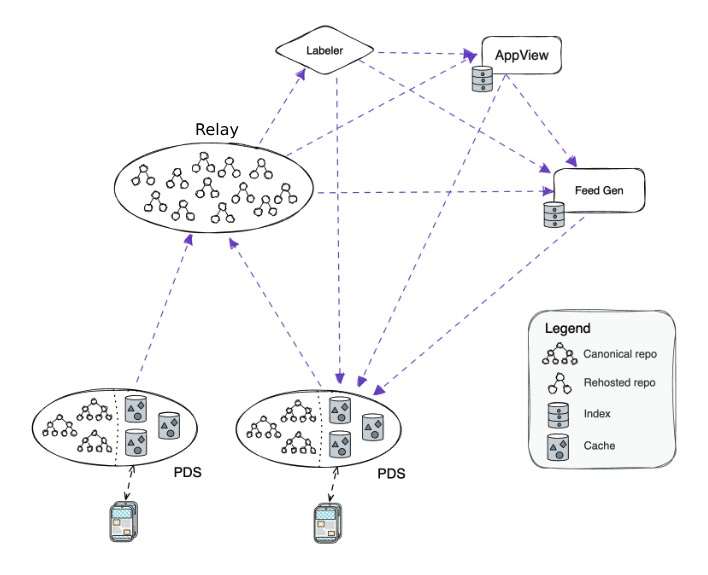

The emergence of platforms like Bluesky has captured the attention of the academic community, offering a glimpse into the future of federated social media for science communication. Bluesky, which operates on a decentralized network, has been lauded for its ability to provide a space where scholars can engage without the algorithmic constraints of centralized platforms. As noted in a recent article from Science titled “As academic Bluesky grows, researchers find strengths and shortcomings” (Smith, 2025), the platform has shown promise in fostering scholarly communication. However, researchers have also identified challenges, such as the potential for fragmented discussions and the need for effective moderation to maintain constructive dialogue.

Bluesky’s growth underscores the potential for federated platforms to serve as dedicated spaces for academic discourse, where researchers can freely exchange ideas and findings without being overshadowed by the engagement-driven priorities of mainstream social media. These platforms also allow users to have greater control over their data and interactions, aligning with the principles of open science. However, to fully realize their potential, federated platforms must address scalability issues and foster inclusive communities that encourage interdisciplinary collaboration.

In response to the shortcomings of centralized platforms, federated social media networks like Mastodon and Bluesky have gained traction. These decentralized platforms operate on interoperable protocols, allowing users to create and manage their own servers with tailored moderation policies. For the scientific community, federated networks offer a unique opportunity to build dedicated spaces for scholarly communication, free from the engagement-driven pressures of mainstream platforms.

Federated platforms also enable greater user control over data and interactions, aligning with the principles of open science. However, challenges remain, including scalability, user adoption, and the potential for echo chambers. To fulfill their potential, these platforms must foster diverse communities and ensure that rigorous, evidence-based content is accessible to broader audiences.

Is Social Media Really the Future of Science Communication?

Looking ahead, the evolution of social media presents several opportunities to enhance science communication. Platforms must prioritize transparency in algorithmic design, enabling users to understand how content is ranked and displayed. Future algorithms could incorporate metrics that favor accuracy and educational value over mere engagement, ensuring that high-quality scientific content reaches wider audiences.

Combining professional oversight with community participation could enhance the reliability of content moderation systems. By integrating expert reviews into community-driven processes, platforms can ensure that complex scientific topics receive accurate representation. Social media platforms could develop incentive structures that reward the creation and dissemination of accurate, evidence-based content.

This might include partnerships with scientific organizations or the introduction of badges and certifications for credible contributors. Supporting the growth of federated social media could provide scientists with alternative platforms tailored to their needs. These networks could serve as hubs for interdisciplinary collaboration, public engagement, and the dissemination of open-access research.

Finally, empowering users to critically evaluate online information is essential for countering misinformation. Social media companies, in collaboration with educational institutions, can promote digital literacy programs that teach users to identify credible sources and interpret scientific claims.

How should we do ?

The shifting algorithms and content moderation policies of Meta, X, and emerging federated platforms mark a critical juncture for science communication. While these changes present challenges, they also offer opportunities to reimagine how scientific information is shared and consumed. By prioritizing transparency, collaboration, and user education, social media can become a powerful tool for bridging the gap between scientific communities and the public, fostering a more informed and engaged society. As the digital landscape evolves, the scientific community must play an active role in shaping the platforms that will define the future of public discourse.

References

Kupferschmidt, Kai (2025). As academic Bluesky grows, researchers find strengths and shortcomings. Science. Retrieved from https://www.science.org/content/article/academic-bluesky-grows-researchers-find-strengths-and-shortcomings

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., Zhang, Y., Lu, J. G., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychological Science, 31(7), 770-780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620939054

Chou, W. Y. S., Gaysynsky, A., Vanderpool, R. C., & Vanderpool, R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and misinformation: How are we doing and what can we do about it? Health Education & Behavior, 47(5), 501-505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120935503

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., & Schudson, M. (2021). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094-1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353-369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2018). Correction as a solution for health misinformation on social media. American Journal of Public Health, 108(S2), S71-S72. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304727

Jarreau, P. B., Dahmen, N. S., Jones, E., & Yammine, S. (2019). Scientists on Instagram: An analysis of engagement and social media practices. Public Understanding of Science, 28(6), 634-650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662519829520

Brossard, D., & Scheufele, D. A. (2013). Science, new media, and the public. Science, 339(6115), 40-41. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1232329